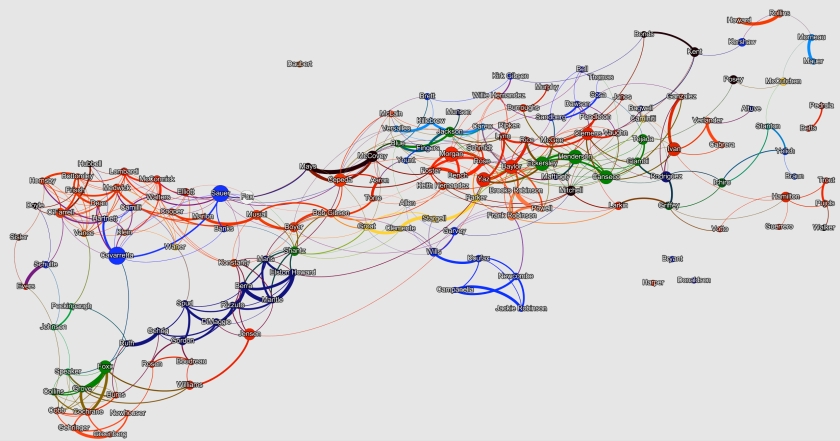

Longtime readers of the Edible Ox will probably have seen one of my posts about networks of NBA MVPs. I recently decided to see what would happen if I extended the same idea to baseball, and the answer is that you get a completely insane version of the graph. Here’s the main image (click on it for a much larger version, which will open in a new tab):

As always, the principles are simple: Every dot is a player who won an MVP award; they’re connected by a line if they played on the same team in the same year (even if neither of them was an MVP at the time); the colors more or less reflect the players’ main teams; the size of the dots reflects betweenness centrality (basically, how well each guy connects other clusters to each other).

I should note that I was less careful about this one than the NBA one. I know more about basketball, and the network involved much less data, so I tried to make sure players actually played together; I even found a case where Moses Malone played 6 minutes on a no-longer-extant team with Bob McAdoo in 1977. That was just too much to ask here; instead, I just consider guys linked if they played on the same team in the same year—which leaves open the possibility that someone was injured, or even that they were traded for each other. If anyone notices any situations like that (or any mistakes—again, not the sport I follow most closely), I’d definitely be interested to hear about them.

That aside, my favorite thing about the graph is how closely it tells the story of baseball history. The players from roughly a century ago—your Ty Cobbs and Tris Speakers—are way over on the left; you’ve got a few decades of dominant Yankees, from Ruth and Gehrig to Mantle and Maris, nearby; in the middle you’ve got the boys-of-summer Dodgers and the classic Pirates and Giants squads; after a tour through the Big Red Machine and 70’s A’s (not to be confused with the 30’s Philadelphia A’s on the other side of the graph), you’ve got the great 90’s players on the Braves, Astros, and Mariners, and finally a sprawling network of today’s stars. It’s not entirely chronological (Mantle and Mays are far apart), but it does a nice job of creating the kinds of discrete clusters you might see on any given night’s Ken Burns or 30-for-30 episode.

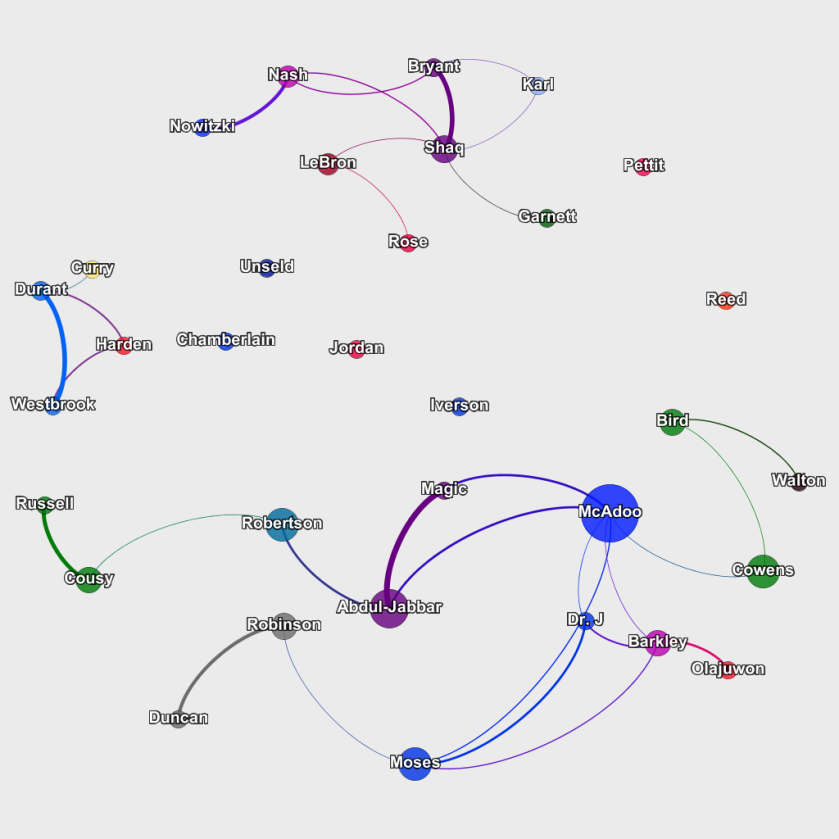

That’s only possible because this graph is way more interconnected than the basketball graph. Here’s that one, for comparison:

Here you see 33 players, of whom 6 never played with another MVP. You’ve also got two large clusters of connected players, plus one small one. In baseball, meanwhile, you’ve only got 4 players who are off by themselves, even though there are 153 people represented on the graph. And the 149 other players are all in one cluster. In other words, a baseball MVP is substantially more likely to play on the same team as another MVP at some point in his career, and you can draw a through-line from nearly any guy to any other guy (e.g., Ty Cobb to Mike Trout goes Cobb -> Jimmie Foxx -> Phil Cavarretta -> Nellie Fox -> Joe Morgan -> Rickey Henderson -> Miguel Tejada -> Iván Rodríguez -> Josh Hamilton -> Trout).

There are a few clear reasons for this heightened connectivity. First, and most important, there are twice as many MVPs in baseball every year, since they award both an NL and an AL MVP. Second, there are more players in professional baseball, which leads to more opportunities to play together. Third, baseball players have longer careers. The average career of an MLB MVP is 16.3 years—or 17.1 if you only count retired players (otherwise Mookie Betts is dragging down the average). For basketball players, those numbers are 14.6 and 15.4, respectively. It’s just a season or two difference, but that’s still about a 10% increase in chances to join a new team for baseball players—plus, this may disproportionately affect those weird late-career years when players in both sports start roaming around.

Finally, baseball is just older in general. They’ve had more chances to acquire the kinds of super-long, very connective careers that, say, the WNBA just hasn’t had time to collect yet. Eddie Collins and Rickey Henderson each played for 25 years, Hank Aaron played 23, and none of their careers overlapped. That’s 73 years of totally distinct careers that don’t even capture several important decades; meanwhile the NBA is 72 years old.

Still, I’ll admit that I was surprised at just how completely connected everyone is. When I first made the graph, a few months ago, there were five players who had no connections. Since then, Betts won and connected to Dustin Pedroia, and Andrew McCutchen played not only with Buster Posey but also, after a mid-season trade, with Giancarlo Stanton, who used to play with the other new MVP, Christian Yelich. Of the remaining loners, three are pretty close to their prime; Kris Bryant got his MVP in 2016, and Bryce Harper and Josh Donaldson got theirs in 2015. It’s entirely possible—based on this network, I’d say it’s probably likely—that they’ll wind up with MVP teammates at some point. And I wouldn’t be surprised if the Betts/Pedroia pair connects to the overall cluster at some point.

And then there’s Jake Daubert. Back in 1911, Hugh Chalmers, some guy who ran a company called Chalmers Automobile, announced that he’d give a free car to the best player in each baseball league. Chalmers died in 1932, the company disappeared in the 1920’s, and the award was discontinued after 1914. But that’s what baseball considers the first MVP award, and Jake Daubert got one in 1913, as the star first baseman of the Brooklyn Superbas (formerly, and later, the Dodgers). I’ll just note that this team also featured a pitcher named Mysterious Walker, whose five year career sent him to five different teams, including the Cleveland Naps and the Brooklyn Tip-Tops of the failed Federal League. You can click on almost any roster in Baseball Reference before 1930 and find a half dozen examples of this kind of nonsense. One more example: Teammates of Daubert in his last season include Bubbles Hargrave, Ivey Wingo, Boob Fowler, Chick Shorten, Greasy Neale, Eppa Rixey, and two different men named Rube. Incredible stuff; our national heritage.

Anyway, the league didn’t start issuing MVP awards again until 1922, so Daubert didn’t have as many opportunities as he might have to collect MVP teammates. And not for lack of trying: He got sick at the end of his 1924 season, and today still holds the unfortunate distinction of being the oldest player to die while still in the majors. This chart gives him another, less gruesome record. Harper, Bryant and Donaldson still have a shot at playing with another recognized great; more than a century after his career ended, Daubert definitely doesn’t. He’s the only MVP in baseball history to have gone it alone.